Dr. Friedman's Office: (210) 880-3000

Retinal Detachments

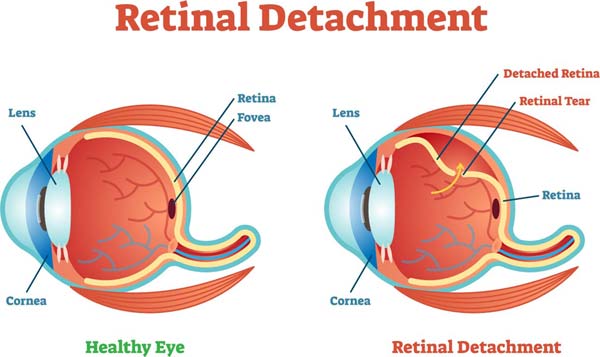

What is a retinal detachment?

An earlier educational section tells the details of retinal detachment and their signs and symptoms. In brief, a retinal detachment involves a “lifting” of the retina off of the back wall of the eye where fluid gets in between the wall (the outer eye wall) and the wallpaper (the retina). A retinal detachment can threaten vision and cause permanent visual loss. One cause of a retinal detachment is a break in the retina that allows fluid to leak underneath. There are many reasons for a break in the retina, but the most common reasons are simply due to aging of the eye. The goal of a retinal detachment repair is to put the wallpaper back on the wall of the eye and make sure it stays there. This also involves treating the break that caused the problem in the first place. There are currently three methods of repairing retinal detachments.

The first means of treatment we will discuss is pneumatic retinopexy. This is often used when the retina has a single, small break that allows fluid to get under the retina. By injecting the eye with a gas bubble that expands and fills some of the space in the eye, the break is pushed up against the back wall. Some surgeons close the break by freezing it using a method called cryotherapy. Other surgeons choose to use a laser and make a scar on the retina that surrounds the break and prevents fluid from getting back underneath.

Pneumatic retinopexy is excellent for people with 1 or 2 small breaks that are confined to a small part of the retina. It requires strict positioning to keep the gas bubble over the tear. Since gas floats to the highest point in the eye (like bubbles in a soda), the retinal tear(s) need to be at the highest point at all times. Good studies have been conducted in the past, and the success rate of pneumatic retinopexy ranges anywhere from 60-75%. One of the benefits is that this therapy can usually be done in the office setting as it does not require an operating room. Also, it is less likely to cause a cataract in the eye for someone that has not had cataract surgery. It is a procedure that is available for a select set of retinal detachments, but it can work very well, and it does not mean that other methods cannot be used in the future.

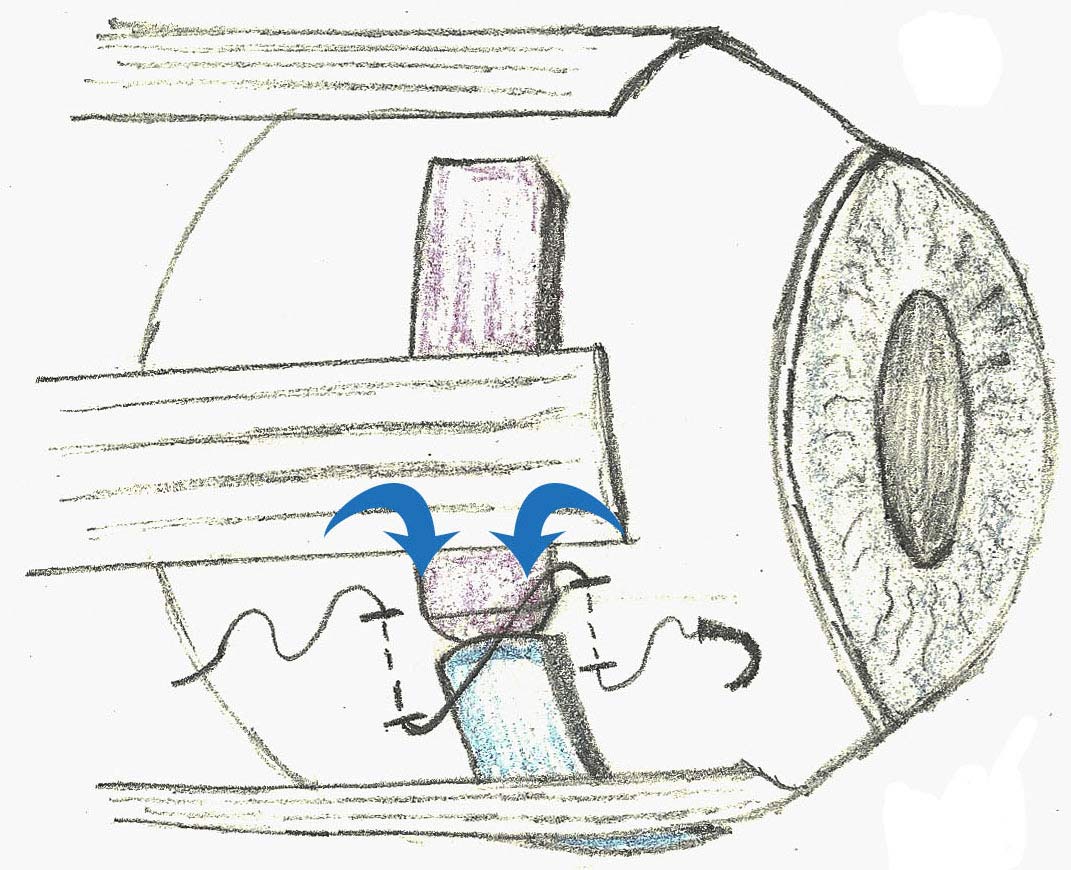

The second method of retinal detachment repair is via scleral buckling. (see figure) Until the 1980’s scleral buckling was the main means of repairing retinal detachments. Instead of bringing the wallpaper of the eye and trying to plaster it back up against the wall, scleral buckling involves moving the wall of the eye inward to meet the wallpaper. By changing the “fluid currents” in the eye and pushing the retinal break closed, the detachment resolves on its own. In today’s retinal detachment repairs with scleral buckles, a silicone band or sponge is placed on the outside of the eye over the area of the retinal break. This is sometimes accompanied by cryotherapy or laser therapy to close off the break and form a scar. Some surgeons will also drain out the fluid under the retina by making a drainage hole on the outside of the eye. This helps the retinal detachment resolve more quickly.

Based on most recent studies, the success rates of scleral buckling can range from 80-90%. This technique is particularly good for people that have retinal breaks at the bottom of the eye. As I explained early, pneumatic retinopexy only works for tears at the top of the eye because the gas bubble will rise to the highest point of the eye at all times. For breaks at the bottom of the eye, a patient would have to stand on their head for about a week to position appropriately in order to prevent recurrence of a retinal detachment. In these cases, a buckle can help by bringing the wall of the eye up to the break, so no bubble is needed.

The last method of retinal detachment repair in common use today is vitrectomy. Retinal breaks occur most often because the gel inside the eye (the vitreous) pulls open a break in the retina. Vitrecomies include taking out some of the gel and thereby removing the traction on the retina. Again, the eye is filled up with a gas bubble to help “re-plaster” the retina up against the back wall of the eye. The surgery allows the eye to be more fully filled with gas to cover all potential breaks. Vitrectomy surgery is once again accompanied by laser therapy or cryotherapy to form a scar around the tear(s) that caused the problem in the first place. By welding the retina back in place, it is less likely for the retina to detach again. The scars take a little time to form though, so the eye has to be filled with gas for this to work.

Most recent studies have shown that this sort of repair is effective 90-95% of the time. Reasons for failure include scar tissue formation or poor positioning on the part of the patient after the surgery. One major drawback to vitrectomy is that it has a predisposition to making an existing cataract a lot worse. In other words, although the vision might be good initially, people who have not had cataract surgery will be more likely to need it in the future.

Many of these therapies can be combined to reach the goal of putting the retina back in place.

Another consideration is the use of a heavier substance in the eye known as silicone oil. Sometimes, a bubble is just not going to hold the retina in place long enough for scars to heal. Either there are too many tears in the eye or the tears are in a bad location to allow good positioning. By using silicone oil, the retina can be “ironed” onto the back wall long enough to allow a good adhesion (think of glue having time to set). The problems with silicone oil in the eye are: 1) it is not easy to see through silicone oil, even with glasses, so vision will likely be poor for the length of time the oil is in the eye and 2) a second surgery has to be done to get the oil out of the eye which requires a return trip to the operating room.

I think a take home message is that you should have a thorough conversation with your retinal specialist about what type of surgery you want. Also, feel free to ask them which technique they are most comfortable performing and what their success rates are. In retina training, there are some programs that teach their students to perform scleral buckling well while focusing less on vitrectomy. In others, the opposite is true and the teaching is very “vitrectomy-heavy”. Realize that there are failures no matter how hard your surgeon tries, but many retinal detachments can be repaired the first time around, and if not the first time, a second surgery can likely complete the repair.

Duncan Friedman

Vitreoretinal specialist,

San Antonio, Texas